The Sao Joao was a Portuguese galleon which came to a sad end in 1552, near Port Edward in southern Kwa Zulu Natal.

She left India in February 1552, overloaded and with only one set of sails. As she sailed down the south east coast of Africa, she was battered by fierce storms, which swamped the ship and she foundered.

Unable to make headway, it headed for a beach, and dropped anchor. Small boats and a longboat were launched, taking the captain and his family to safety first. The boats were lost, and the rest of the crew and passengers clung to anything that floated in the hopes of surviving.

Within hours, the Sao Joao had broken up, and all its merchandise, said to be the richest and largest ever to leave India, was gone.

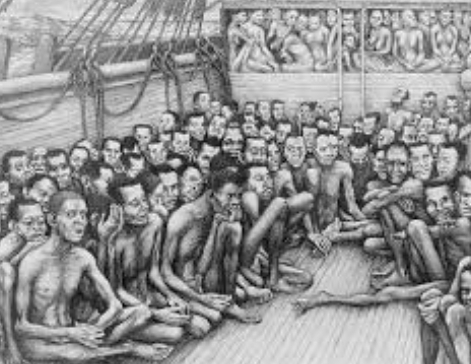

500 souls survived, of them 300 were slaves. The captain Manuel de Sousa Sepulveda, his wife, the noblewoman, Dona Leonor (sometimes written as Donna Leonora or Dona Lionar), their three children, and his brother in law, Pantaleo de Sá were among the survivors.

Noble men and women were not suitably dressed for Africa

Local people appeared in the distance a few days later, but did not make contact, possibly because they feared the strangers, but a few days later, a group of people leading a cow arrived at the area where the survivors were camped. Trade was attempted, but did not happen, and they left with their cow.

The closest Portuguese settlement was at Maputo Bay, later named Lourenco Marques, now again named Maputo, in Mozambique, many hundreds of kilometres to the north. The decision to start walking to Lourenco Marques was made, and 12 days later, lead by the ship’s pilot, André Vas, their journey started. Vas carried a banner with a cross on it, at the head of the party. The captain and his family followed, as did 80 Portuguese passengers and one hundred slaves.

Dona Leonor was carried on a litter by slaves. Her brother was at the rear of the group, with soldiers in case they were attacked while en route.

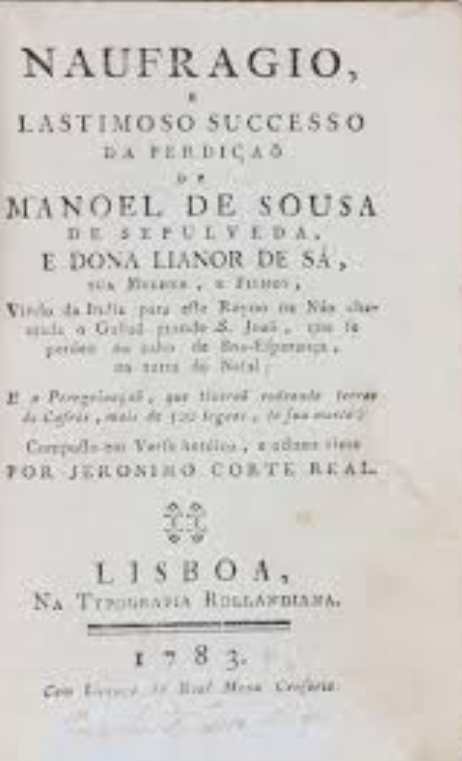

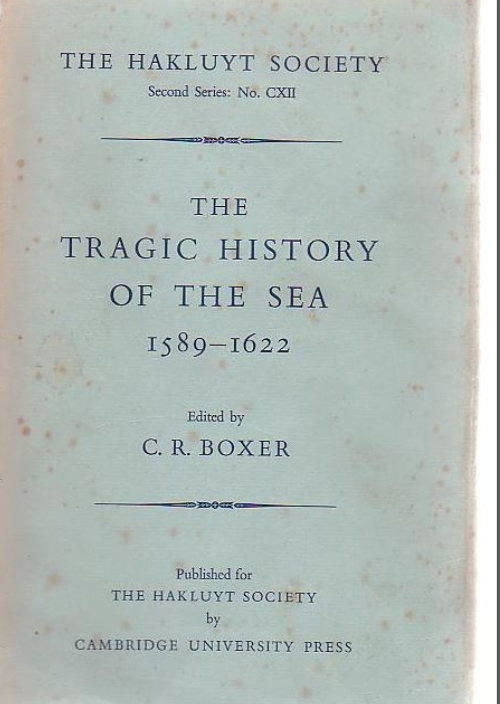

The anonymous writer of the account of the journey, The Naufragio, was supposedly told the story by a crew member, but it is full of inconsistencies and anomalies which cannot be verified. The writer stated that they did not meet anyone with whom they could barter, and that they lived off ship’s stores, fruit that they found and fish. As a group of 120 persons reached the Nkomati River, that account is suspect, especially as the writer also recorded that they fought with local people, and that the captain had killed a man in a fight. That the survivors took provisions by force from villages that they passed is probably closer to the truth.

At the Nkomati River, they were met by a chief, who suggested that they wait there until a ship arrived. This was agreed to, but as the survivor party was large, the people were allocated to different villages, and were not allowed to keep their weapons. Once separated, the survivors were robbed and thrown out of the villages.

The captain and his family had stayed with the said chief, but decided to move on with the rest of the group. Further north, probably near the Limpopo River, they were attacked and robbed of their clothes. This was the undoing of Dona Leonor. Having survived a walk of over a thousand kilometres through African bush and jungle, hunger, and all sorts of hardships that a noble woman had never dreamed of in her worst nightmares of ever enduring, her nakedness was the last straw. She buried herself in the sand, refused to move, and she and her children died of starvation. Her husband, who seemingly had gone mad from his wife’s actions, disappeared into the wilds and was never seen again.

Eventually, eight Europeans and seventeen slaves reached Inhambane and were rescued by a Portuguese trading vessel.

Records of survivors from later shipwrecks tell of meeting Indian and European Sao Joao survivors who broke away from the north bound group and stayed. It is also presumed that many slaves would also have wanted to stay behind in the villages that they passed through, and did so.

The slaves which survived, may have stayed behind with local Africans they met along the way.

A strange part of this historical event, is that Pantaleao da Sá, not only survived, but was in possession of much gold and jewelry, which he was supposedly given by a chief, because he saved the said chief’s life. The story reeks of untruths, and the true providence of the riches will never be known, but it is presumed that he robbed his fellow castaways of their possessions.

The story of the Sao Joao survivors became a famous tale in Portugal, and the sad tale of Dona Leonor also became part of Camões’ epic poem, The Lusiads (Os Lusiadas).

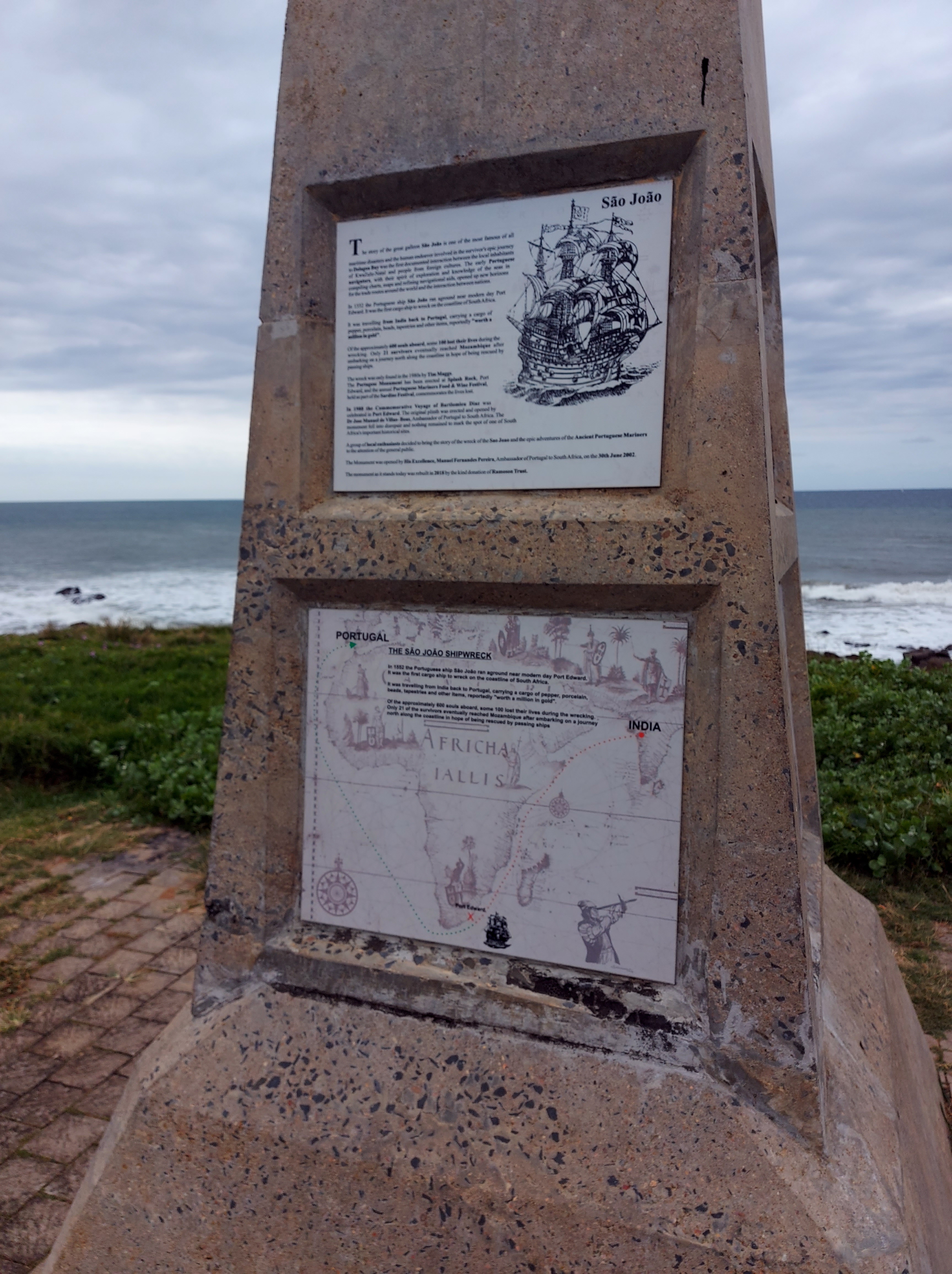

Having become such an important part of Portugal’s maritime history, when it was confirmed that the Sao Joao was wrecked near Port Edward, and not further south near Port St Johns as was originally thought, the Portuguese government sponsored a monument to the victims of the disaster.

The monument tells the story of the Sao Joao and her survivors.

Lots of questions and inconsistencies I agree, but then again why spoil a good story with facts!?

Thanks for sharing this fascinating piece of history with us, Kathryn.

Interesting to note that the Portuguese already had a presence in the subregion a century prior to the Dutch settling at the Cape yet had a much lesser influence beyond the Lebombos despite their “head start” in the colonisation of this part of the continent.

LikeLike

Hello!

What really fascinates me is that the Portuguese named Natal, didn’t stick around, but the name stuck!

LikeLike