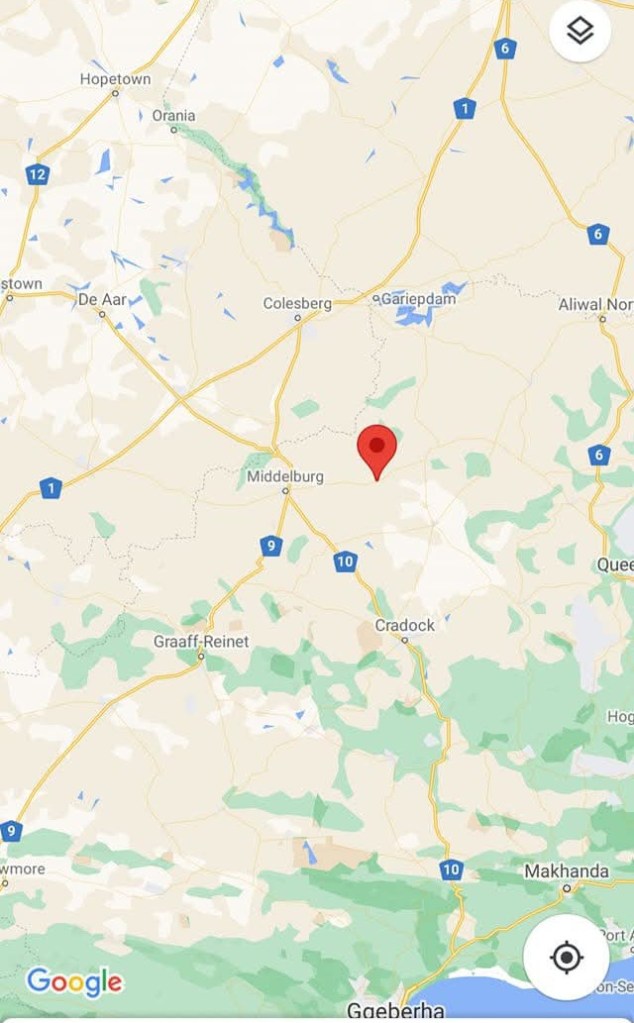

Once upon a time , on a hot, dry, windy day, in April 1780, literally in the middle of nowhere, a Dane claimed a spot of land in what is one of the harshest areas on earth to farm. He recorded the event by carving the story on a huge boulder which is now in a cattle kraal, in the Karoo, in South Africa.

Die Teebus and Die Koffiebus.

As my travel companion, Elsa van der Merwe asked me as we drove on dusty Karoo farm roads looking for this rock – how do I even know about stuff like this? How I knew of this was that in a little read book on South Africa, l had come across the story, forgotten about it, but now that I was in the area, the memory had been triggered, and I had to find where this countryman of mine had recorded that he had been there.

We had been invited to present our book, The Guide to Port St Johns at the Boekbedonnerd Festival held in Richmond in the Northern Cape. Being us, we stayed off the highways and took the longer narrower roads, and saw a lot more of the Karoo than most people do. We had overnighted in Middelburg, and I had enquired at the local tourism office where this rock was. They had no idea, but I could try calling the local family of the same surname. I did. No luck, yes, she had heard the story, but no, now the family seat was a few miles away, in the hamlet named for the family, and the carved rock was not there. She gave me another name and number to call, and that person also had a vague recollection of the story, but was clueless, but suggested as a possibility, to try going down a particular farm road, and ask the farmers there. So here we were, driving through miles and miles of Karoo farmland. Elsa had a few days earlier decided that her real vocation in life was that of a rally driver, and drove accordingly, with me beside her pretending to see lots of rocks that she had to slow down for.

We saw dozens of the (now) ubiquitous Springbok, the odd (I think) Grysbok, plenty of tortoises, all intent on crossing the road. Why did the tortoise cross the road? Dunno – to me it looked pretty much the same on both sides. There were plenty of Springhares (Pedetes capensis) too – unfortunately all dead. Despite the name, with their long back legs, which make them kangaroo-like, Springhares are not related to hares or rabbits. They are mostly nocturnal, and not too clever – they unsuccessfully try do their amazing jumps in front of vehicles at night, getting blinded by the headlights. The result: every few kilometres there was another squashed springhare roadkill.

We also saw the remains of a springbok that had tried to clear a fence, but had gotten stuck in it. Poor thing, what an awful way to die, hanging in a fence by your legs in that incredible heat. You may think it would have quickly died of thirst – but probably not – springbok rarely drink water, they get enough moisture from the plants they eat, so the poor animal would have suffered a long time.

About 150 years ago, millions of springboks lived in this part of the world, and they migrated across the barren land in search of food, akin to swarms of locust; in herds so huge, that it makes the Masaai Mara Wildebeest migration look like a non-starter. Unfortunately, the trekbokke, as they were called, were almost wiped out by farmers and hunters, leaving the numbers of springbok much reduced, and the springbok you now see as you drive through the Karoo are mostly farmed. For more on that bit of history, see: https://galavantingwithkathryncostello.blog/2022/11/07/the-trekbokke-of-the-karoo/

herds of springbok trekbokke.

Security is tight on farm roads. They have to be, as many farmers have been murdered, and stock theft is also a huge concern. Cameras are on regularly spaced poles. Gates and booms have to be opened manually: you get out the car, facing straight into a camera, then move slowly and open the boom. Should you be a baddy, or just look suspicious, the local farmers will all be alerted immediately via their security network.

A farmer came towards us, we flagged him down, and again asked about the rock. Again, he wasn’t too sure, but said: ‘ask Oom Piet, his is the farm a few kilometres away, he may know. ‘Oom’ is ‘uncle’ in Afrikaans, and in the Afrikaans culture you always, as in always, call men who are older than you ‘Oom’; and older women, ‘Tannie’ (aunt). The rule applies whether you are ten or fifty years old – if the other person is older, call them ‘oom’ or ‘tannie’. Or Meneer or Mevrou, if you don’t want to be too familiar.

We arrived at Oom Piet’s gate. He had a pack of dogs, that were crosses of the long-legged fox terrier variety. They were good watchdogs – the type of dogs that even I, as a generally non-scared doggy person has huge respect for. I got out of the car, but stood next to the open door, just in case the mutt barking on top of the wall decided to be really dutiful and collect me as a trophy for his master. There was no sign of anybody being home, so I encouraged the dogs to keep barking, effectively calling their master. The master heard the warning barks and came to investigate.

In my best Afrikaans, I explained why we were there. Oom Piet, said: ‘Wag net a bietjie, ek gaan trek my skoene aan.’ (Hang on a minute, I’m going to put my shoes on). We took the hint, and also changed from flip flops to proper trainers.

Oom Piet came back, and led us off into the bush/ cattle kraals, where his rather nasty looking cattle stared at us (don’t laugh, I’m scared of cows) traversing their paddocks. Piet headed towards a slight rise that was littered with huge rocks, squinting as he tried to remember which was the interesting one. Pulling bushes away from possibilities, he at last called out that he had found it. And there it was, with the legend carved into the rock in Dutch:

‘Anno 1780 April ik ben die plaas heft aangelyt. AGSB uyt Denemark. Sprenghane als sant’ (The year 1780 April. This farm was founded by me AGSB from Denmark. Locusts like sand.)

The story of ‘AGSB’, is that he, a Dane, by the name of Schomb, had travelled up from the Cape to this near desert area, and had claimed / been allocated the land as his own, engraving his claim on the boulder.

This chappie, Andreas Gottlieb Schomb lived in Kongsdal, north of Copenhagen. The surname is more German than Danish, but then there was a large German population in that area in the 1700s. No-one seems to know what the ‘B’ at the end of his initials stand for.

The story of how Andreas came to South Africa, is a sad and a happy one. As researched by his descendants, Andreas had a fight with his brother Guillaume. Guillaume fell out/ was pushed out of a second story window, and Andreas thought he was dead. The only way to escape the authorities, was to get as far away as possible. He boarded a ship bound for the Cape, probably from Hamburg, as there are no records of ships being Cape bound from Copenhagen.

He arrived safely, became a resident of Stellenbosch, and at some stage bumped into his ‘dead’ brother, Guillaume. To add to the ‘lived happily ever after story, they put their names down for land when it was offered by the Dutch authorities, and were successful, being allocated a piece of land near Middelburg in 1780, and to commemorate the occasion, he engraved the legend on one of the many large boulders strewn on the rise above the land.

The area is harsh, with near desert conditions. That they eked out some kind of living on that land is a testament to their persistence and hard work.

Andreas married a woman of French descent, Johanna Sophia Viljoen of Tulbagh (where many French Huguenots had settled). They had a large family, probably 6 sons and 3 daughters, and in doing so, became the proginator of the Schoombie family in South Africa today.

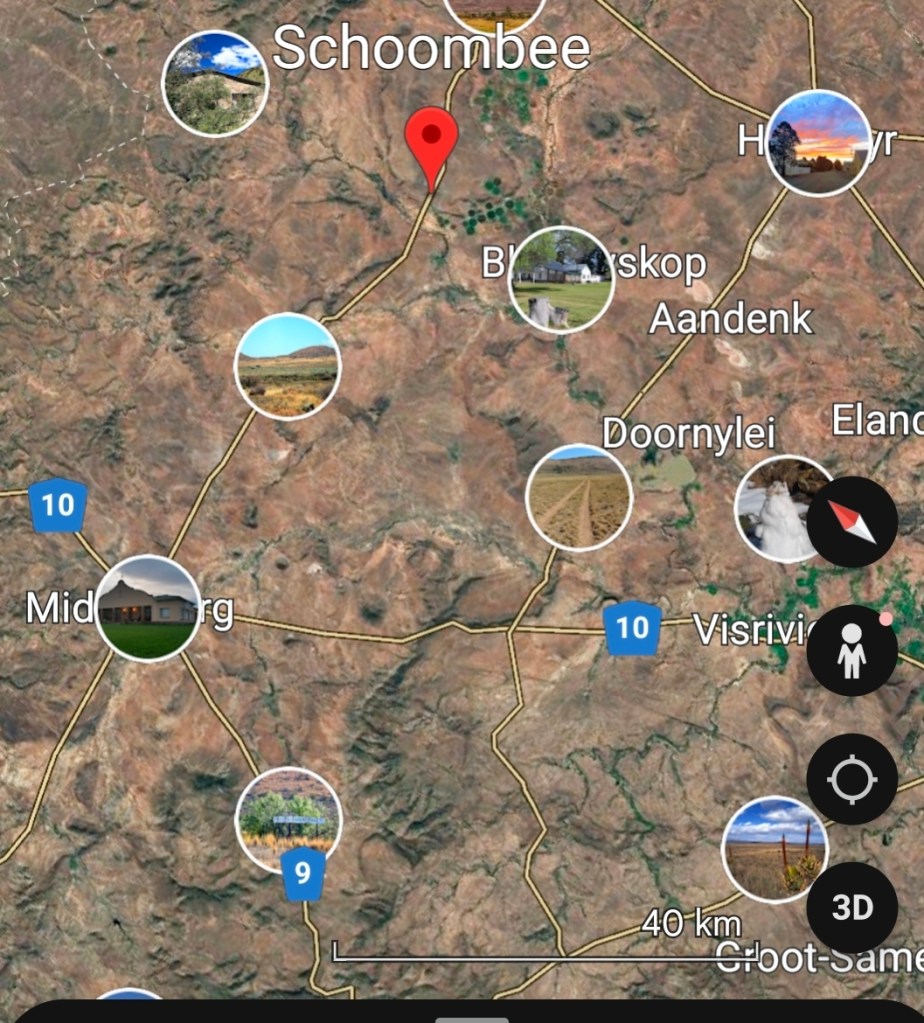

Today, there is a village named Schoombee in the Karoo, not too far from the engraved rock. It is a farming area, and the village attracts tourists for hunting, bird watching, and peace and tranquility.

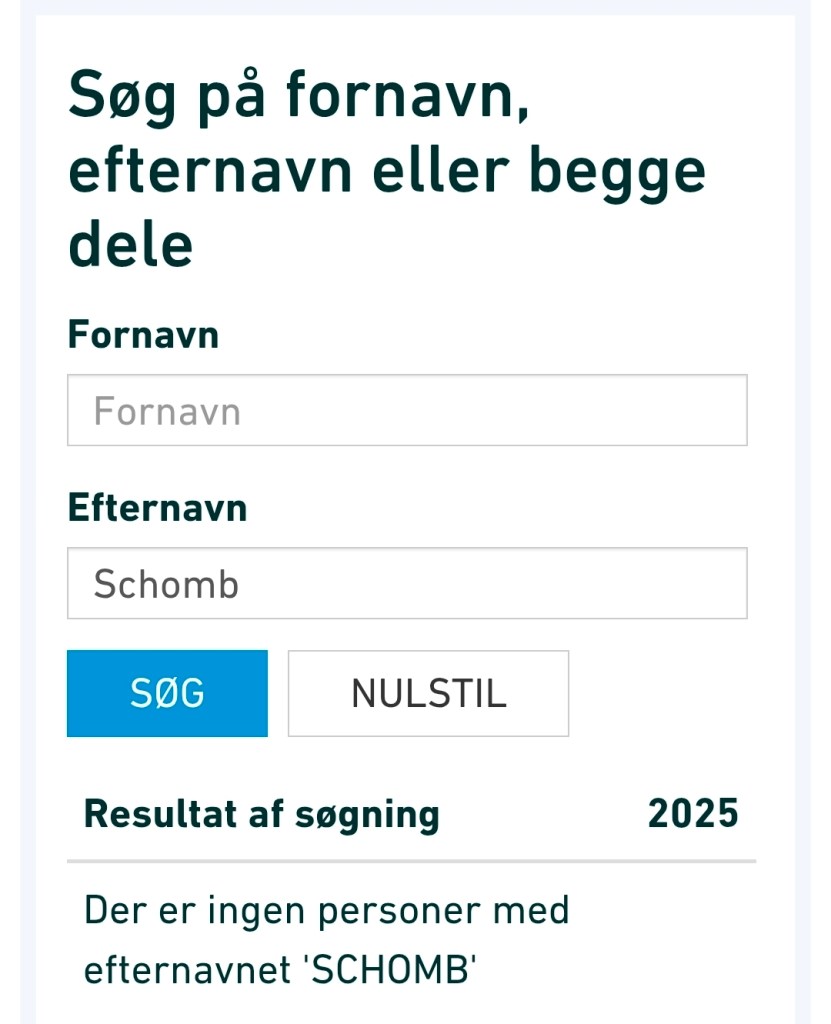

In Denmark, the name Schomb has died out; genealogical name searches have resulted in finding no-one by that name.

South Africa today is a wonderful hodge podge of bloodlines and cultures. Schoombie /Schoombee isn’t the only South African surname with Danish roots; Danes were quite common in the early days of South Africa. Krotoa, more commonly known as Eva, who was Jan van Riebeeck’s translator, married the Danish explorer, Pieter van Meerhof. Meerhof was the Dutchified version of Havgaard ( Meer/ Hav = Sea, Hof / Gaard = Land or property). Their daughter in turn married into the Saayman/ Zaaiman family. The Afrikaans surname ‘van Tonder’, is derived from an immigrant who came from the town of ‘Tønder’. Erasmus, Krog, Moller, and Hansen and many more surnames, especially those that end in ‘sen’ probably have Danish roots, just as Schoombie does.

Note: To protect the farm owner’s privacy, ‘Oom Piet’ is not his real name. Should he want tourists coming to his farm regularly, he’ll probably advertise what is on it.